Studying AMQP protocol

AMQP protocol (Advanced Message Queue Protocol) is an asynchronous message exchange specification which allows for interoperability between different platforms. That is one of the main features provided by AMQP. Besides the possibilities to achieve the same with JMS (another specification that provides asynchronous message exchange), JMS rely on proprietary solutions with some drawbacks depending on the context. This post’s goal is to provide summary content around what I had studied about AMQP, so I won’t dive into explaining the differences between JMS and AMQP here. There was a really nice article written by Mark Richards in the past, but the link to that article is currently broken at the time of writing the update to this post (2025).

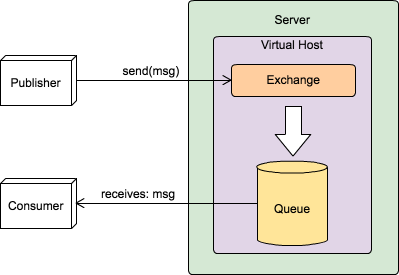

General AMQP’s architecture

Before start using any AMQP broker, it is worth understanding the main components from AMQP model and how they interact with each other. The three main components are:

-

Exchange: this component receives messages and routes them to proper message queues.

-

Message queue: responsible for keeping messages and to forward them to binded consumers.

-

Binding: binds exchanges with message queues defining routing rules.

Besides the main components, it’s also important to know the entities involved in the process of message exchange in an AMQP server:

-

Publisher: the entity responsible for sending messages to the broker. In AMQP terms, the publisher usually sends messages to an Exchange which in turn decides which message queue to forward them. A service or application here is a good example of a publisher.

-

Consumer: consumes from message queues (likely to perform some processing based on message’s content), e.g. another decoupled service that processes messages from the queue.

-

Broker: is the queues server which implements the AMQP specification, e.g. RabbitMQ.

The figure that follows shows tha basic components addressed so far and how they relate to each other:

And now lets take a dive in more details on each component:

Message Queues

Message queues have some properties that when combined together can be used to build conventional entities from middlewares. Some properties that are worth studying are:

-

private or shared: this property defines if it’s a private message queue with just one consumer allowed to listen for messages or if it’s a shared queue where more than one consumer is allowed to listen for messages. Queues declared as exclusive are considered private queues.

-

durable or temporary: defines if a queue will be destroyed or not when rebooting the server.

-

client-named or servernamed: if the client defines the name of the queue during it’s declaration it will be client-named. Otherwise, if the server by itself take the responsibility for naming the queue, it will be considered servernamed.

When combining such properties, one can create some entities already known and used by the most middlewares as follows:

-

store and forward queue: an ordinary kind of queue which just keeps the messages and deliver them among consumers relying with round-robin algorithm. They are usually durable and shared.

-

private reply queue: kind of queue that receives the messages and forwards them to just one bound consumer. They are usually temporary and server named.

-

private subscription queue: collects messages from different sources and forwards them for just one bound consumer. They are usually temporary, private and server named.

Exchanges

-

Receives all messages created by publishers and send messages to Queues following pre-defined rules which are called Bindings. It is possible to declare nameless default Exchanges and also Exchanges with names so they can be bound with Queues.

-

Exchanges are abstract models which allows to add extensibility to AMQP servers (even though at the cost of interoperability).

-

There are direct and topic kinds of exchanges.

Routing Key

- Is a virtual address that allows for the Exchange to decide how to route any message (a field in the header of an AMQP message).

- It is easy to make an analogy with a mail server where the routing key is the email address, the queue is the inbox and the exchange is a MTA (mail transfer agent) which knows how to route the message based on mail address.

Binding

- Defines the relationship between exchanges and queues which can be achieved in different ways. It must be declared with a name or pattern which can be used during routings performed by exchanges. Before routing to an specific queue, the routing-key header’s field is compared with the name defined in binding rule. Such comparisons can be direct or can also be through pattern matching (i.e.

rabbit.*). Using such pattern, messages which come with routing keysrabbit.fastorrabbit.sloworrabbit.anything, will be redirected to the queue defined on binding rulerabbit.*. A*matches with a word and#matches with zero or more words.

Queue declaration examples

Creating a shared queue

A shared queue can be created using the default exchange just by not declaring it’s exchange name. Below are some pseudo-code snippets to clarify the example:

Declaring a queue with app.atticus name:

Queue.declare

queue=app.atticus

Consumer:

Basic.Consume

queue=app.atticus

Publisher:

Basic.Publish

routing-key=app.atticus

Creating a reply queue

A reply queue is usually declared as temporary and private so its name is declared by the broker. Its name is returned in Ok responses to the client.

Example of reply queue declaration:

Queue.declare

queue=<empty>

exclusive=TRUE

// server response

S:Queue.Declare-Ok

queue=tmp.star

Sending a message to the queue:

Basic.Publish

exchange=<empty>

routing-key=tmp.star

Declaring a pub-sub queue

Allows for messages with routing-keys with a matching binding to be delivered to a specified queue. The AMQP protocol does not define a subscription entity.

The following snippets present how to do it:

Queue.Declare

queue=<empty>

exclusive=TRUE

S:Queue.Declare-Ok

queue=tmp.vogel

Queue.Bind

queue=tmp.vogel

TO exchange=amq.topic

WHERE routing-key=DAS.IST.EIN.*

Consumer:

Basic.Consume

queue=tmp.vogel

Publisher:

Basic.Publish

exchange=amqp.topic

routing-key=DAS.IST.EIN.VOGEL

Looking to the snippets above, one can see that the examples are using statements which looks like Class methods (such as used by object oriented programming languages). Such structure does not follow this model by chance. The AMQP spec defines such statements which in a similar way aiming to abstract and ease the protocol design given that Middleware implementation is often too complicated.

The most interesting point here is that if you study the RabbitMQ’s API (which is an AMQP implementation broker), you should note that the sintax defined by the API’s methods are similar with low level statements defined by the protocol.

Following is an example of a Java code sending messages to a queue:

public class Send {

private final static String QUEUE_NAME = "hallo";

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException, TimeoutException {

// creates RabbitMQ connection factory

ConnectionFactory factory = new ConnectionFactory();

factory.setHost("localhost");

// effectively creates a connection with declared factory

Connection connection = factory.newConnection();

// create a channel to start switching messages with broker

Channel channel = connection.createChannel();

// declares a queue as durable and shared

boolean durable = true;

channel.queueDeclare(QUEUE_NAME, durable, false, false, null);

// defines the prefetch count as 1 so the queue does not accepts more messages

// until the current received message won't be processed

int prefetchCount = 1;

channel.basicQos(prefetchCount);

// concats all strings sent as arguments for this simple app

String message = getMessage(args);

// publish a message to declared queue.

// here we are using a default exchange because the name of an existent exchange won't set

channel.basicPublish("", QUEUE_NAME,

MessageProperties.PERSISTENT_TEXT_PLAIN,

message.getBytes());

System.out.println(" [x] Sent '" + message + "'");

channel.close();

connection.close();

}

private static String getMessage(String[] args) {

if (args.length < 1) {

return "Hallo Welt!";

}

return joinStrings(args, " ");

}

private static String joinStrings(String[] strings, String delimiter) {

int length = strings.length;

if (length == 0)

return "";

StringBuilder words = new StringBuilder(strings[0]);

for (int i = 1; i < length; i++) {

words.append(delimiter).append(strings[i]);

}

return words.toString();

}

}

And now an example of a message consumer which listens for messages delivered to the “hallo” queue:

public class Recv {

private final static String QUEUE_NAME = "hallo";

public void receive() throws IOException, TimeoutException {

// creates RabbitMQ connection factory

ConnectionFactory factory = new ConnectionFactory();

factory.setHost("localhost");

// effectively creates a connection with declared factory

Connection connection = factory.newConnection();

// create a channel to start switching messages with broker

Channel channel = connection.createChannel();

// declares a queue as durable and shared

boolean durable = true;

channel.queueDeclare(QUEUE_NAME, durable, false, false, null);

System.out.println(" [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C");

// defines the prefetch count as 1 so the queue does not accepts more messages

// until the current received message won't processed

int prefetchCount = 1;

channel.basicQos(prefetchCount);

// Creates the callback defined for message consuming

Consumer consumerCallback = new DefaultConsumer(channel) {

@Override

public void handleDelivery(String consumerTag, Envelope envelope,

BasicProperties properties, byte[] body)

throws IOException {

String message = new String(body, "UTF-8");

System.out.println(" [x] Received '" + message + "'");

try {

doWork(message);

// acknowledge the message so Rabbitmq can delete the message from queue

long deliveryTag = envelope.getDeliveryTag();

channel.basicAck(deliveryTag, false);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println(" [X] Message weren't processed");

} finally {

System.out.println(" [X] Done");

}

}

private void doWork(String task) throws InterruptedException {

System.out.printf(" \t[X] starting processing task: %s \n", task);

for (char ch : task.toCharArray()) {

if (ch == '.') Thread.sleep(1000);

}

}

};

boolean autoAck = false;

channel.basicConsume(QUEUE_NAME, autoAck, consumerCallback);

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException, TimeoutException {

Recv recv = new Recv();

recv.receive();

}

}

This was another edition of the log-book of devadventures.

The main idea here wasn’t to get into details of Publisher or Consumer implementation. The code presented before was just added as an example of AMQP broker communication.

In a next post I will dive deeper into RabbitMQ usage examples.