Creating a terminal emulator from scratch

In this post I write about how I implemented an over simplified terminal emulator that helped me understanding how it works behind the scenes while also learning many interesting things about Linux along the way. Writing a full blown terminal is far from an easy task, so this post is just the tip of the iceberg. Although, interesting enough for me to spark the curiosity about how things work.

The whole source code for this project is available on GitHub.

This idea about writing my own simplified terminal started when I stumbled upon some weird characters sequence that I found when setting up a command prompt variable used for formatting purposes. Moving back from MacOS to Linux as a desktop led me to decide using bash again instead of zsh and I noticed that my prompt was missing git branch info as well as some nice color formatting. Since I actually have my dotfiles on GitHub, my first reaction was: “why is this missing from my .bashrc file?”. Fortunately I have this saved as a GitHub gist, and that is what I found:

function git_branch_name () {

branch=$(git symbolic-ref --short HEAD 2>/dev/null)

if [ -n "$branch" ]; then

echo "($branch) "

fi

}

PS1="\[\033[38;5;4m\]\u@\h\[\033[0m\]:"

PS1=$PS1"\[\033[38;5;083m\]\w\[\033[0m\] "

PS1=$PS1"\[\033[38;5;122m\]\$(git_branch_name)\[\033[0m\]$ "

At least for me, the PS1 content isn’t much readable and that was the start of everything about this journey.

Just for the records, this can be easily generated using Bash Prompt Generator, however in any case, I just updated my “dotfiles” with the bash prompt formatting that I like (here is how I setup my dotfiles).

Before proceeding to the next sections, I want to mention that there a lot of similar blog posts out there and some are really good (expect some overlaps). My favourite, which helped me with the first steps is the Terminal anatomy. Nevertheless, I find it easier to read now that I did my own research on things that were not clear to me when I first found the Terminal anatomy blog post. The other two posts that I think are worth reading in case you want to go deeper (I just skimmed through them for now), are listed in the references at the bottom of this page. And last but not least, I think The Secret Rules of the Terminal by Julia Evans might also be pretty cool. I haven’t read that yet, but I am considering buying it at some point.

The weird PS1 variable

First of all, this PS1 thing is weird enough for people unfamiliar with the Linux shell and terminal (yes shell and terminal are not the same thing and I will dissect this in this post). To start off, PS1 is not even an environment variable. It is a shell variable (more specifically, a bourne shell variable that bash uses). From the bash manual:

The primary prompt string. The default value is ‘\s-\v$ ’. See Controlling the Prompt, for the complete list of escape sequences that are expanded before PS1 is displayed.

But once this variable purpose is demystified, look at these weird stuff like \[\033[38;5;4m\]\u@h\[\033\[0m\].

There’s a lot going on there, so let me break it down:

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| \[ | Starts a string of non-printing characters. |

| \] | Closes this non-printing characters string. |

| \033[ | Starts the SGR parameters. \033 can also be represented as \E or \x1b in different contexts. |

| 38;5;4m | The SGR parameters. This is formatting the foreground color using the 256 color style (as opposed to ANSI colors) with light green (number 004 hexa) |

SGR stands for Select Graphic Rendition and it is an ANSI instruction used to define graphical attributes of text in the terminal.

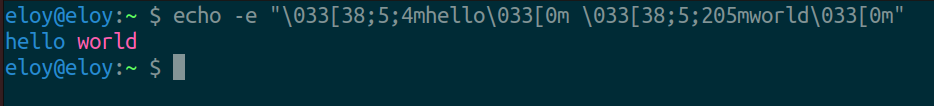

It is used with the m finalizer and accepts multiple parameters such as color, bold, and reset. Look that all of these escape characters aren’t used only for the purposes of formatting the prompt, but to format any character anywhere in the terminal. Just try the following command on the terminal:

echo -e "\033[38;5;4mhello\033[0m \033[38;5;205mworld\033[0m"

The output should look like follows

My purpose with this post is far from going deep on how this notation actually works. There are good documentation – actually source of truth – available as well (in case you want to validate what ChatGPT tells you). For more about the syntax of this formatting sequence, check Bash Manual / Controlling the Prompt.

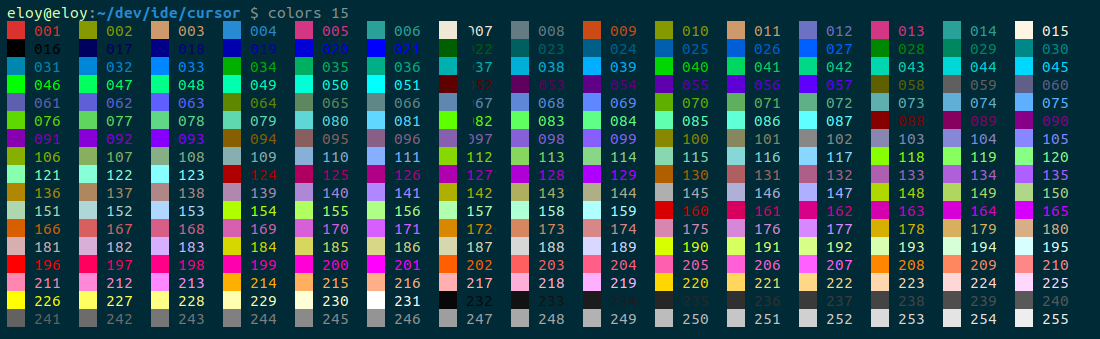

In relation to the colors, I ended up creating a bash script just for fun to print a 256 terminal color palete for me which prints something like follows in the terminal when I type colors (if you want it, just have a look at the source code at colors.sh in cmdcenter GH repository):

This helps me picking up the right color number to set as SGR parameters and I think it is also fun to see them printed on my terminal :)

While I was nearing completion of this post, I realized that someone else had also written about building a custom command line, including a similar script to print the palette—though theirs was implemented in Python: Build your own command line with ANSI escape codes. That said, I still prefer my own approach.

Where is the terminal?

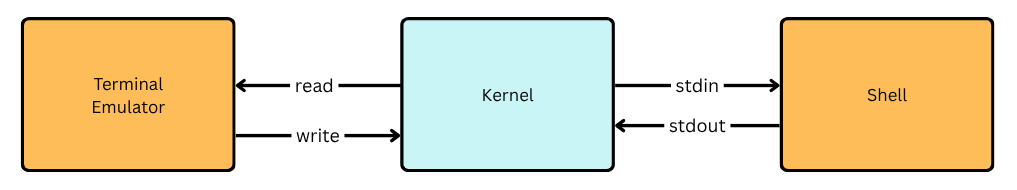

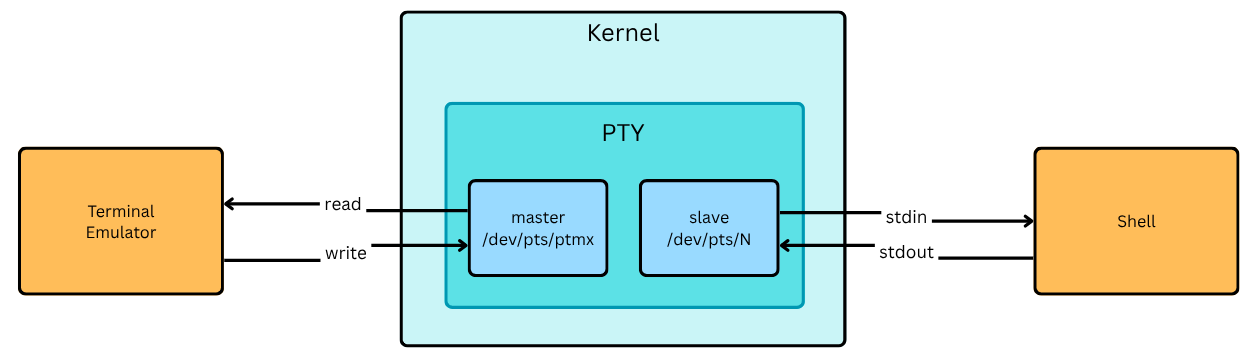

Fair enough, whoever is reading this might be a bit impatient to start typing code to create a very simple terminal on their own. However, some concepts must be understood before jumping into the code. I think that the best way to understand all the moving parts of a terminal emulator is to start with simpler mental models first. The diagram below shows a very simplified abstraction of terminal emulator architecture that should help building up confidence before coding.

The main components

The terminal emulator

The terminal emulator is a graphical application that allows you to type in the commands and interact with your *nix operational system. Examples of a terminal emulator are gnome-terminal, Alacrity, ST (Simple Terminal), iterm from MacOS, xterm and many many more. At the time of this writing I found a page with a list of 30+ Linux Terminal Emulators.

The name terminal emulator may sound odd, but it comes from early days —before computers— when TTYs (teletypewriters) were used to distribute stock prices over long distances in realtime 1. These devices evolved into CRT-and-keyboard terminals connected to time-shared computers, where the mainframe managed text manipulation like backspacing and cursor movement. Unix later abstracted these roles into software, enabling both physical and “pseudo-terminals” to interact with the system.

The shell

The shell is just one type of process you can run in a terminal, with popular examples including bash, zsh, and sh. But terminal emulators aren’t limited to shells—they can host any interactive program, such as ssh, tmux, or language REPLs like python or irb. These programs receive user input from the terminal emulator, process it, and send output back—often formatted using ANSI escape sequences to control text color, style, cursor positioning, and more.

The kernel

This is where the Linux kernel comes into play—handling all the low-level details that allow terminal emulators to communicate with processes like bash, ssh, tmux, and others. At a high level, this interaction is managed by the TTY subsystem using the PTY (pseudo-terminal) abstraction, which bridges the gap between the terminal emulator (on the primary side) and the process (on the secondary side). It’s a complex and fascinating part of the system, and we’ll explore it in more detail later on.

PS: I am using the words primary and secondary to refer to the PTY sides which is also consistent with what I read in the Terminal anatomy blog post. However, some sources refer to them as master and slave respectively, which I find a bit outdated.

Creating the terminal emulator

From the three boxes being currently used as the simple mental model of a terminal emulator, the terminal emulator itself is what will be implemented here. Remember, this is a graphical application so the first thing to create is a window that can render characters that a user types in and characters coming from the shell. To achieve that, the code below initializes an SDL window, which will serve as the canvas for the mini terminal.

#include <SDL2/SDL.h>

int main() {

SDL_Init(SDL_INIT_VIDEO);

SDL_Window* win_sdl = SDL_CreateWindow(

"Mini Terminal",

SDL_WINDOWPOS_CENTERED,

SDL_WINDOWPOS_CENTERED,

1200, 600, SDL_WINDOW_SHOWN);

int running = 1;

SDL_Event event;

while (running) {

while (SDL_PollEvent(&event)) {

if (event.type == SDL_QUIT) {

running = 0;

} else if (event.type == SDL_KEYDOWN) {

if ((event.key.keysym.mod & KMOD_CTRL)

&& event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_c) {

running = 0;

}

}

}

SDL_Delay(10);

}

SDL_DestroyWindow(win_sdl);

SDL_Quit();

return 0;

}

Compiling this code requires the SDL2 library, which can be installed on Ubuntu with sudo apt install libsdl2-dev. After that, you can compile it using:

gcc -o mini_terminal mini_terminal.c -lSDL2

Then run it with ./mini_terminal. You should see a window like the one below:

Creating the bridge to the shell

At this point this terminal emulator window has just one functionality: it can be closed. Not exactly a terminal emulator yet, but now I can start connecting the dots with the Kernel and the shell.

The next step involves having the terminal emulator to read from and write characters to the shell. To achieve this, I will use the pty library that is available on Linux. The PTY (pseudoterminal) is an abstraction representing a bridge between the terminal emulator and the shell. These two programs communicates through a bi-directional asynchronous communication channel provided by the PTY2. The terminal emulator writes to the PTY primary side, while the shell reads from the PTY secondary side. This allows the terminal emulator to send commands to the shell and receive output back. Letś take another step improving the mental model with more details.

In more concrete terms, the PTY is a pair of virtual devices: the primary and the secondary. The primary side is what the terminal emulator interacts with, while the secondary side is what the shell interacts with. The PTY primary side is represented by /dev/ptmx, which is a multiplexer file that allows multiple terminal emulators to connect to the same PTY. The secondary side is represented by /dev/pts/N, where N is a number assigned to each PTY secondary. All of this will make more sense as we dive deeper into some more code (this runs before the terminal emulator starts listening for SDL events).

pid = forkpty(&primary_fd, NULL, &term, &win);

if (pid == -1) {

perror("Error creating pseudo-terminal");

return 1;

}

if (pid == 0) {

printf("Initializing the shell...\n");

int res = create_pid_file();

if (res > 0) {

return res;

}

execlp(getenv("SHELL"), getenv("SHELL"), NULL);

perror("execlp");

exit(1);

}

The core idea behind the creation of the PTY is to use the forkpty function, which creates a pseudo-terminal and forks a child process. This function opens the /dev/pts/ptmx file, which is the primary side of the PTY, and returns a file descriptor that can be used to read and write to the PTY. On the other hand, the child process stdin and stdout are directly connected to the PTY secondary side, which is represented by /dev/pts/N.

| Path | Description |

|---|---|

/dev/pts/ptmx |

A file/device to which the terminal emulator gets a handler that it uses to read and write to. |

/dev/pts/N |

N is a number bound to a process responding to the terminal emulator (e.g., bash). |

A short experiment with PTY

As an experiment, if you type tty on the terminal, you will get the corresponding /dev/pts/N file, e.g. /dev/pts/19. Then if I go to another terminal and cat /dev/pts/19, whatever I type on the previous terminal gets printed by cat output.

Rendering characters read from the PTY

The missing part to have a minimal working terminal emulator is to handle the communication between the terminal emulator and the shell, as well as rendering the characters on the screen. The code below shows how to read from the PTY primary side and render the characters on the SDL window. The first thing to do is to create a buffer to hold the characters read from the PTY primary side, i.e. /dev/pts/ptmx and append that to the lines buffer global variable (something done by append_line_to_lines_buffer() function).

int running = 1;

SDL_Event event;

char buf[256];

while (running) {

// reading the shell output from the primary file descriptor

fd_set fds;

FD_ZERO(&fds);

FD_SET(primary_fd, &fds);

struct timeval tv = {0, 10000}; // 10ms

if (select(primary_fd + 1, &fds, NULL, NULL, &tv) > 0) {

ssize_t n = read(primary_fd, buf, sizeof(buf) - 1);

if (n > 0) {

buf[n] = '\0';

append_line_to_lines_buffer(buf);

}

}

// ommitting the rest of the code for brevity

Once the line buffer is updated with next line read from the PTY, the terminal emulator needs to render the characters on the screen. This involves processing the line buffer and drawing the characters using the SDL graphics library as follows:

SDL_SetRenderDrawColor(renderer, 0, 0, 0, 255);

SDL_RenderClear(renderer);

int y = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < num_lines; ++i) {

SDL_Surface* surface = TTF_RenderText_Solid(

font, lines[i], (SDL_Color){255, 255, 255});

SDL_Texture* texture = SDL_CreateTextureFromSurface(renderer, surface);

SDL_Rect dst = {10, y, surface->w, surface->h};

SDL_RenderCopy(renderer, texture, NULL, &dst);

SDL_FreeSurface(surface);

SDL_DestroyTexture(texture);

y += FONT_SIZE;

}

SDL_RenderPresent(renderer);

SDL_Delay(10);

Notice that lines[i] is the line buffer holding all the characters read from the PTY, which is appended by the append_line_to_lines_buffer() function declared as follows:

void append_line_to_lines_buffer(const char* text) {

if (num_lines < MAX_LINES) {

snprintf(lines[num_lines++], MAX_LINE_LENGTH, "%s", text);

}

}

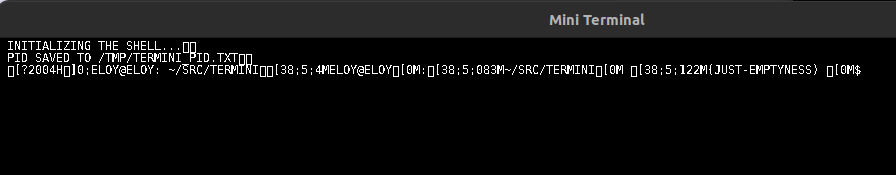

Now, running this code should give back something that looks more like a terminal emulator, although it is completely barebones. For now it only renders characters coming from the shell, but it does not handle user input yet.

Handling user input

To handle user input, the terminal emulator needs to read characters typed by the user and write them to the PTY primary side. This is done by capturing keyboard events from SDL and writing the characters to the PTY primary file descriptor. The code below shows how to handle keyboard events and write the characters to the PTY (this is just an improvement in the loop that was previously created to handle SDL events):

while (SDL_PollEvent(&event)) {

if (event.type == SDL_QUIT) {

running = 0;

} else if (event.type == SDL_TEXTINPUT) {

write(primary_fd, event.text.text, strlen(event.text.text));

} else if (event.type == SDL_KEYDOWN) {

if ((event.key.keysym.mod & KMOD_CTRL)

&& event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_c) {

running = 0;

} else if (event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_RETURN) {

write(primary_fd, "\n", 1);

} else if (event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_BACKSPACE) {

write(primary_fd, "\x7f", 1);

}

}

}

The terminal emulator now renders characters typed by the user and text that comes from the shell. Although it is far from perfect (if you test it you will notice that it does not handle cursor movement, line wrapping, or any other advanced features), it is a good starting point to understand how a terminal emulator works. But it is time to close the loop here and connect everything with the initial question about the PS1 variable and the terminal emulator.

Where are the ANSI escape sequences?

Looking closely to what is being rendered, there are many characters printed as little boxes or question marks. This is because the terminal emulator is trying to print nonprinting characters. I need to handle them in a way that they can be visible to the user for educational purposes. The code below shows how to handle ANSI escape sequences and render them as visible characters in the terminal emulator.

void escape_and_append(const char* input) {

char escaped[MAX_LINE_LENGTH * 4]; // buffer maior para acomodar escapes

int j = 0;

for (int i = 0; input[i] != '\0' && j < MAX_LINE_LENGTH - 4; ++i) {

unsigned char c = input[i];

if (c == '\n') {

escaped[j++] = '\\';

escaped[j++] = 'n';

} else if (c == '\t') {

escaped[j++] = '\\';

escaped[j++] = 't';

} else if (c < 0x20 || c >= 0x7f) { // não imprimível

j += snprintf(&escaped[j], 5, "\\x%02x", c);

} else {

escaped[j++] = c;

}

}

escaped[j] = '\0';

append_line_to_lines_buffer(escaped);

}

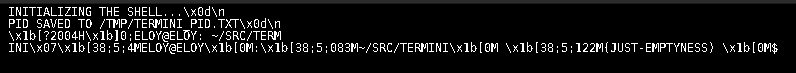

Now where I call append_line_to_lines_buffer() I will use escape_and_append() instead and that is what the user should be able to see now:

If you look closely, you will see that before the username, there is the escape sequence \x1b[38;5;4m which is the SGR parameter for the light green color. This is the same sequence that was used in the PS1 variable to format the prompt. The same applies to the other escape sequences that are printed in the terminal emulator.

All of these escape characters are then interpreted by the terminal emulator to apply the corresponding formatting (e.g., changing text color) when rendering the output. Some terminal emulators may rely on terminfo or termcap databases to map these escape sequences to specific terminal capabilities, but in this case, the terminal emulator is handling them directly (Alacrity does the same).

Going even deeper

At this point one might still ask: what and where in the kernel the whole communication actually happens? The answer to this question is that the TTY subsystem in the Linux kernel is responsible for managing terminal devices, including PTYs. The TTY subsystem provides a framework for terminal drivers, which handle the low-level details of reading and writing data to terminal devices.

The main components of the TTY subsystem that I had the chance to explore in the Linux kernel source code are:

-

TTY Drivers: These are responsible for interfacing with the actual terminal hardware or emulated terminal devices (like PTYs). They implement the necessary functions to read from and write to the terminal.

-

Line Discipline: This is a layer that sits between the TTY driver and the terminal user. It is responsible for processing input and output data, handling things like line editing, job control signals, and more.

The workflow of the TTY subsystem can be summarized as follows:

The PTY primary, typically accessed by the terminal emulator via /dev/ptmx, receives data written by the emulator. This data is handled by the TTY subsystem in the kernel, where the TTY driver manages the low-level I/O logic and interacts with the line discipline, which processes the data (e.g., echoing, buffering, signal generation). On the other end, the PTY secondary (e.g., /dev/pts/N) is connected to a process like bash, which communicates through standard input and output. The kernel links both ends, making the shell believe it’s connected to a real physical terminal.

Next steps

As next steps I plan to implement some of the missing features in this terminal emulator, such as:

- Handling cursor movement and line wrapping

- Implementing basic text editing features (e.g., copy, paste, and delete)

- Adding support for ANSI escape sequences to control text formatting (e.g., bold, underline, and colors)

This whole exploration also sparked my curiosity about the inner workings of the ptmx and how to register devices in the kernel. I am planning to write a post about that in the future, so stay tuned!

Final thoughts

While exploring the terminal emulator architecture, I found it fascinating how many layers of abstraction are involved in the process of rendering characters on the screen. Reading from the work of others in this space has provided me with valuable insights into the complexities of terminal emulation and the underlying systems at play.

Besides that, I would like to say how much some AI tools have helped me especially in understanding the Linux kernel source code components related to the TTY subsystem. Nothing beats reading from the source of truth, i.e. the source code. If you want to explore it by yourself, you can find the TTY subsystem code in the Linux kernel source code under drivers/tty/. The PTY implementation is in drivers/tty/pty.c, and the TTY core is in drivers/tty/tty_io.c.

References

- Terminal anatomy

- The TTY demystified

- Build your own Command Line with ANSI escape codes

- The Secret Rules of the Terminal

- List of 30+ Linux Terminal Emulators

- IBM - Time-Sharing

- Linux kernel source

Footnotes

-

The TTY Demystified (see history section) ↩