Dissecting Asynchronous Responses in Servlet based Java Applications

On a daily basis, if you are working on a Java based application, chances are high that your application provides some REST APIs built with some framework that provides abstraction on top of Servlets. Although Servlet based applications are present in many Java based web applications or services, it is easy to get lost in the terminology especially when it comes to async processing and non-blocking I/O.

Every backend Java developer knows what is a Servlet and I hope, also knows how it works. It is a staple technology in the Java world and as everything else, it is also easy to take it for granted. As with a terminal emulator, which I investigated on a previous post, there is always more than meets the eyes happening under the hood.

Driven by curiosity, I made the decision to take a deep dive on what is behind Servlet’s asynchronous support down to the Linux system calls.

What you will find in this post

After my little adventure on this topic, I was able to better understand how Tomcat handles ~10,000 concurrent connections with a smaller number of threads using sockets with non-blocking I/O and how asynchronous processing works under the hood at both Tomcat internals and syscall level.

On a personal note, I find joy on investigating what is behind simple things we use everyday. Yesterday was about terminal emulator, today is about Servlet, tomorrow may be what is behind NodeJS event loop (spoiler: I’ve been playing with libuv already - the library that underpins Node’s event loop). For the everyday use of Servlets, it should be a boring topic, but finding the little universe behind it is something else, it is fascinating (at least for me).

Some history first

One of the things I like about the deep dives, is that through source codes and low level APIs, chances are high that I can also find some interesting history behind the thing being investigated. For Servlets in particular, why async support was added circa 2009? What were the problems being tackled? What was happenning around 2009 and before? What were the alternatives to solution given that we can use till today? This is archeology of software engineering, and to me this is as cool as reading and writing code.

To understand the context around how async processing came up in Servlets, I travelled back in time around 2006 where AJAX was the thing and everyone was excited about Web 2.0. Before the final Servlet 3.0 spec bringing the asynchronous support to the backend, many different approaches were taken to achieve the same or similar problems being solved by Servlet 3.0. Some examples are the Eclipse Jetty project and Comet (a style of event-driven, server-push data streaming, which the name was coined by Alex Russell in a post published in 2006 called Commet: Low Latency Data for the Browser).

Here comes the challenges

All of that cool stuff available at that time in order to create more interactive web applications such as AJAX, came also with a new set of challenges for the backend. One single client could open multiple connections to the server, and multiple requests could happen concurrently, increasing the load on the server. Just imagine how much the load would increase on a page that was supporting 1000 concurrent requests and suddenly with more interactivity, 10 additional requests per client would be made via AJAX for that same page. That would go beyond what Tomcat could handle at that time leading to a resource starvation issue with unsatisfied customers.

A better and standardised way of handling slow processing and long-lived connections was clearly needed. To start overcoming these challenges, one of the proposed changes for the Servlet 3.0 was suggested as “Async and Comet support” (see JSR-315). The main focus of this proposal was to add asynchronous request processing support, which by itself should help with the resource starvation problem as well as leveraging the Comet style applications.

Non-blocking I/O support was also considered and further improved with Servlet 3.1 allowing for non-blocking reads and writes of request and response respectively. However, that wouldn’t yet be the full non-blocking solution that we know today with e.g. Spring WebFlux with Netty, or what is provided by other stacks such as NodeJs. In case you want to know more about the history and see alternatives proposed such as the one by the Jetty’s author, I left some good references at the end of this post.

Abstractions

When I learned about the Servlet’s async support a long time ago, I didn’t use it straight away. When I actually had to use the Servlet Async support, I was using an abstraction on top of Servlets provided by Spring Web MVC (to keep it shorter I will call it only Spring Web).

One of the questions I had at that time was: if the response is left open and it is processed by another thread other than the worker, how does Tomcat know how to send the request to the right connection (i.e. to the right client)? I know that it is not reasonable to dive deep into internals on every abstraction that I use in a daily-basis. Doing so would make me the most unproductive developer, so as most people do, I accepted that Tomcat just works as expected and moved on. However, the curiosity was still there.

Alright, so now that Spring is staple framework for Java projects, is it still worth understanding the nitty-gritty details of Servlets and Tomcat? I think so. Regardless of using Spring Web or directly using Servlets (although I expect most projects to be using some abstraction on top of Servlets), the principles remain the same and a solid understanding about it helps clearing out common misunderstandings about asynchronous vs non-blocking I/O support. Besides, this model is also replicated at some extent by other stacks outside of the Java world.

DeferredResult, Callable and WebAsyncTask as controller return types for async support. When returning these types, Spring Web uses Servlet's 3.0 async support in order for the response to be returned from a separate thread (it works a bit different from the example in this page since it relies on dispatching mechanisms). It also allows for returning reactive types, although they are all adapted to an equivalent async result type (e.g. a DeferredResult for single value results).

Enough with history, time to see some code

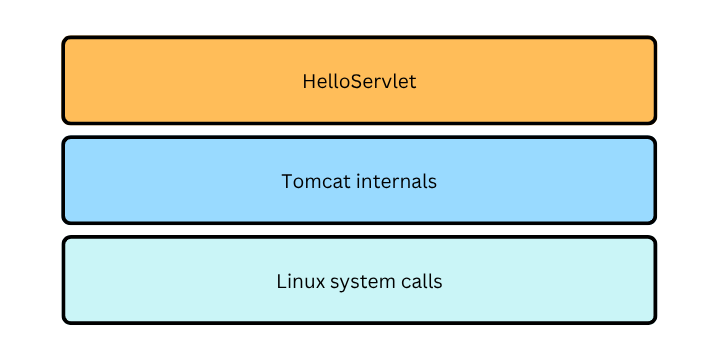

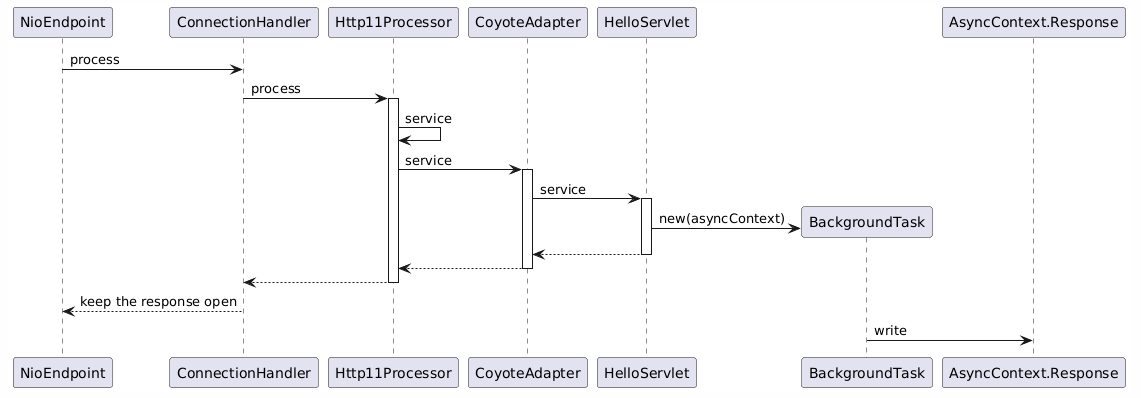

To navigate this exploration, I present it all in a top-to-bottom style, following the diagram shown below. Here I start explaining what HelloServlet is doing, then start diving into Tomcat’s internals down to the operational system calls via APIs and syscalls. In my case, my exploration started with the Servlet while looking at strace logs first.

HelloServlet

The servlet’s purpose here is very simple:

- Handle a request to

/helloendpoint - Start an asynchronous context

- Hand-off the request processing to a new thread named

custom-thread. That is enough to free the current the Tomcat’s worker thread - Finally send the response to the client from

custom-thread– a task perfomed byBackgroundTask– responsible for completing the request processing.

The complete source code for this simple Servlet project is available as another repository on my GitHub: asyncservlet. I recommend downloading it in case you want to run some of the commands that I share in this post.

@WebServlet(value="/hello", name="helloServlet", asyncSupported = true)

public class HelloServlet extends HttpServlet {

private final static String CUSTOM_THREAD_NAME = "custom-thread";

@Override

public void service(HttpServletRequest req, HttpServletResponse res) {

System.out.println("Handling the request in thread: "

+ Thread.currentThread().getName());

AsyncContext asyncContext = req.startAsync();

asyncContext.setTimeout(10_000);

new Thread(

new BackgroundTask(asyncContext),

CUSTOM_THREAD_NAME

).start();

}

}

The background task simply sleeps for four seconds and is responsible to write to the response and to complete the asynchronous processing. The following snippet shows the background task.

private record BackgroundTask(AsyncContext asyncContext) implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

System.out.println("Processing async in thread: "

+ Thread.currentThread().getName());

Thread.sleep(4_000);

var res = (HttpServletResponse) asyncContext.getResponse();

res.setContentType("application/json");

writeResponse("Hello, World", 200);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

writeResponse("db error", 500);

} finally {

asyncContext.complete();

}

}

private void writeResponse(String message, int status) {

var res = (HttpServletResponse) asyncContext.getResponse();

try {

res.setStatus(status);

res.getWriter().println(message);

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

}

Running the example

If you want to run the code, in order to have a smooth experience I recommend you install SdkMan in case you still don’t have it. Most of my Java projects come with a .sdkmanrc with the Java version being used for the project and in order to use the right version from the terminal, all that is needed is to run sdk env (IntelliJ recognises it straight away picking-up the right JVM for the project – of course it expects you to have the JVM installed).

Once you have the Java 21 installed, you can simply run the following commands:

mvn clean package

java -jar target/asyncservlet-1.0-SNAPSHOT-shaded.jar

I am also using wrk as a benchmarking tool in order to compare asynchronous vs synchronous processing. Here is its GH project page. With wrk you can send concurrent requests using multiple connections as in the snippet below. On this example I am creating 10 connections and 20 threads with a duration of 10 seconds. This should allow one to see how many requests can be handled within this period of 10 seconds given the conditions set in the parameters.

wrk --timeout 10s --latency -t20 -c10 -d10s http://localhost:8080/hello

Tomcat internals

First things first, in this section I examine two separate aspects of Tomcat: the low-level networking components and HTTP request pipeline. The former manages socket creation, polling and event dispatching while the latter actually process the request by parsing it, applying filters, invoking the Servlet’s service method and processing the response.

Before diving in code or logs, lets examine the networking level starting with the actors that collaborate to accept connections and handle the request.

The actors behind a request

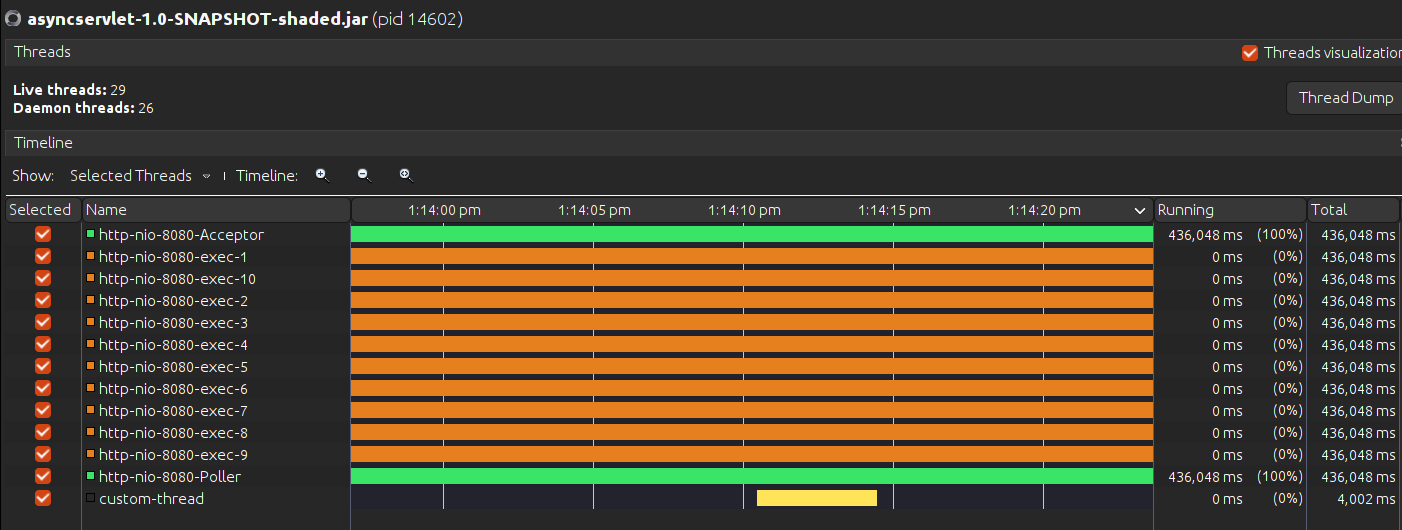

I think the easiest way to actually see the actors at play, is by actually sending requests to /hello endpoint and monitoring Tomtcat’s threads by using a tool like VisualVM or jconsole.

The following image, captured from VisualVM while processing a request to /hello endpoint, shows the threads that are relevant for the purposes of this post.

Straight to the point, the actors are the Acceptor, the Poller, some Workers and the Custom Threads. Here is the breakdown of each one:

- Acceptor: accepts new connections from clients and hand the request off to the poller by adding a

PollerEventto thePoller’s internal queue. - Poller: the poller blocks for one second waiting for new events on the queue, read an event without blocking if there is one available or it is “woken-up” by the

Acceptorwhen it adds a newPollerEventtoPoller’s queue. Whenever there is an event to process, the poller offloads the processing to a worker thread, also known from Tomcat’s Javadocs and source code as container thread. I will keep calling it worker thread. - http-nio-8080-exec-N: this is actually an instance of Tomcat’s worker thread. Tomcat starts with a pool of ten threads ready to process incoming requests. By default, it can create a maximum of 200 requests.This information can be obtained from Tomcat’s documentation, but can also be retrieved from JMX Tomcat’s

ThreadPoolattributes (VisualVM doesn’t come with the MBeans tab out-of-the-box, so if you want to see this for yourself, you have to install MBean plugin for VisualVM). - custom-thread: this is the thread I am creating from within

HelloServlet#servicemethod. and I refer to it as simply custom thread.

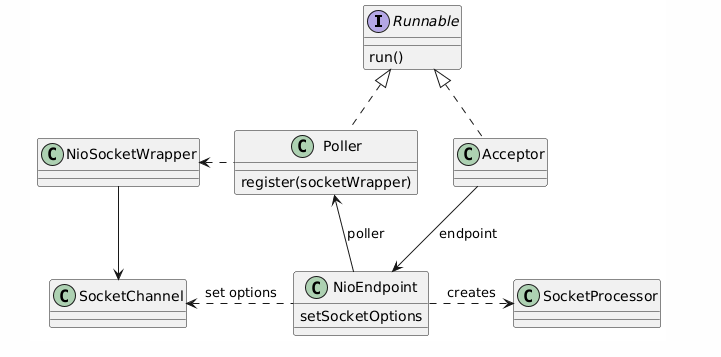

The networking level classes

Now to put things in perspective, the actors previously described are all instances of some of the classes depicted in the class diagram below. I consider NioEndpoint the main class in this diagram because Poller and Acceptor are all its inner classes. Besides, they all collaborate to handle the low-level networking work, and coordinate the communication via Worker threads. As an attempt to shortly describe what is in this picture, these classes collaborate to accept connections, handle the request to the workers and start the HTTP request pipeline via SocketProcessor.

Linux System calls

When I first started exploring how Tomcat handles requests under the hood, I wanted to see how the custom thread was actually sending the response back to the right client. And I started from examinig Linux system calls using strace. Although the logs can be sometimes huge, knowing the basic system calls and what to look for in the logs, can help a lot in understanding what is going on with a software component even if you don’t have the source code. In my case, that actually guided me on what to expect from Tomcat’s source code. In case you don’t know what strace is, here is a short description from strace’s man page:

It intercepts and records the system calls made by a process and the signals a process receives

Okay that can be a bit abstract. The second paragraph of the description section is better and even inspiring:

strace is a useful diagnostic, instructional, and debugging tool. System administrators, diagnosticians, and troubleshooters will find it invaluable for solving problems with programs for which source code is not readily available, as recompilation is not required for tracing. Students, hackers, and the overly-curious will discover that a great deal can be learned about a system and its system calls by tracing even ordinary programs.

I can relate with this beautiful description! Especially when it says “a great deal can be learned about a system and its system calls by tracing even ordinary programs”. This is what this blog post is about. I was debugging an ordinary Servlet.

A prime on the system calls

The most interesting system calls that I show in the logs collected after sending a request to /hello are:

- epoll_create1

- epoll_ctl

- epoll_wait

- fcntl

The other system calls are self explanatory so I won’t cover them here.

The epoll API

The calls epoll_create1, epoll_ctl and epoll_wait are all part of epoll API. According to epoll’s man page, epoll is an I/O event notification facility. In a maybe overly simplified idea, the epoll can be use to watch file descriptors (e.g. pipes, sockets and devices are represented as file descriptors in Linux and you can think of them as handlers).

In other words, you give epoll a list of file descriptors to monitor for changes (e.g. the socket is ready for reading or writing) and wait for events to happen. One more thing: epoll_wait blocks while waiting for a notification, so here I was able to see that the Servlet’s async support is intrinsicaly blocking. However, of course Tomcat doesn’t just sit there forever waiting for notifications. There is actually a loop where it indirectly (via NIO Selector) epolls for one second. On the next iteration it may have happened that an event became ready to be processed and that’s when the following system call happens (notice that the last argument is 0 – timeout is set to 0 and it doesn’t wait to get the event notification):

epoll_wait(9, [{events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=11, u64=xx}}], 1024, 0) = 1

The following snippet is the logic that runs in a loop (a while true) within the Tomcat’s Poller.run() method. Notice that the logic in the if block (when the condition is true) is what actually maps to the epoll_wait with a timeout of zero seconds.

if (wakeupCounter.getAndSet(-1) > 0) {

// If we are here, means we have other stuff to do

// Do a non-blocking select

keyCount = selector.selectNow();

} else {

keyCount = selector.select(selectorTimeout);

}

I won’t expand on the logic around the wakeupCounter, but the summary is that it will be used as a mechanism to wake up the poller to do a non blocking select (selectNow) or stop waiting for an event. This counter is incremented every time there is a new poller event initiated by the Acceptor when a new request comes in and that can lead to a wakeup operation on the selector which in turn will wake-up the selector that is waiting with a one second time out (the else block from previous snippet will be woken up):

// class Poller

private void addEvent(PollerEvent event) {

events.offer(event);

if (wakeupCounter.incrementAndGet() == 0) {

selector.wakeup();

}

}

For more about the epoll system call, I think the blog post “The method to epoll’s madness” is awesome. I also recommend this nice overview about it, written by Julia Evans, “Async IO on Linux: select, poll, and epoll”.

fcntl

I will be short on this one because I honestly didn’t explore it much, but the bottom-line is that it performs operations on open file descriptors. The reason I am mentioning it here is because there is an interesting call in the strace logs:

fcntl(11, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

This command is simply setting the socket’s file descriptor property O_NONBLOCK, which means that this file descriptor is non-blocking I/O. Alright so we have non-blocking I/O support, right? Not too fast! That is a property set for the connection only, which means that each time one tries to read from the socket and there is nothing to read, instead of blocking it returns a EAGAIN flag and the program continues until next attempt to read.

This system call is made exactly when a new connection is accepted by the Acceptor and some options are set before adding it to the current connections map and being wrapped by SocketWrapper class (mentioned in the class diagram). This operation is achieved by the following line of NioEndpoint.setSocketOptions method:

socket.configureBlocking(false);

I want to emphasize again that the non-blocking mechanism here is used on the connection only. If you have a logic that blocks running by the custom thread, that thread will be blocked, waiting for whatever it has to wait unless you use a non-blocking library to do the work. As an example, one could use WebClient from Spring WebFlux to send a request to another service which would be performed in a non-blocking way.

Connecting the dots

Now that I have provided context about the low-level networking Tomcat’s classes and the relevant system calls, it is time to dissect a request. The first thing to do then is to start the service and send a request to /hello. While debugging Tomcat, I started the service with the command strace but the tracing can be started after the service is up and running. To do that, just provide the service’s process ID (PID) with -p strace option.

Starting the service with strace:

strace -ttt -f -o trace.log -e trace=network,desc -s 2000 \

java -jar target/asyncservlet-1.0-SNAPSHOT-shaded.jar

Then, all I have to do was to send a request to /hello, wait for the response and stop the process so that the log don’t keep growing indefinitely (it grows fast). Here is a summary of the tracing log with what is relevant for this debug:

144471 5438.553 epoll_create1(EPOLL_CLOEXEC) = 9

144523 5438.555 accept(8, <unfinished ...>

...

144523 5440.167 <... accept resumed>{sa_family=AF_INET6, sin6_port=htons(59396), ...), sin6_scope_id=0}, [28]) = 11

144523 5440.175 fcntl(11, F_GETFL) = 0x2 (flags O_RDWR)

144523 5440.175 fcntl(11, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

144523 5440.177 accept(8, {sa_family=AF_INET6, sin6_port=htons(59400), ...), sin6_scope_id=0}, [28]) = 12

...

144522 5440.178 epoll_ctl(9, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 11, {events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=11, u64=126985003073547}}) = 0

144522 5440.178 epoll_wait(9, [{events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=11, u64=126985003073547}}], 1024, 0) = 1

144522 5440.178 epoll_ctl(9, EPOLL_CTL_DEL, 11, 0x737e05ffe514) = 0

...

144512 5440.201 read(11, "GET /hello HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: localhost:8080\r\nConnection: keep-alive...", 8192) = 695

144512 5440.218 write(1, "Handling the request in thread: http-nio-8080-exec-1\n", 43) = 43

...

144513 5440.221 write(1, "Processing async in thread: http-nio-8080-exec-2\n", 49) = 49

144513 5444.231 write(11, "HTTP/1.1 200 ...", 136) = 136

...

144522 5444.232 epoll_ctl(9, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 11, {events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=11, u64=11}}) = 0

Accepting the connection

All that happens here are calls made at the low-level networking I/O, but some of them are also the result of what is started from the HTTP request pipeline. The first line is self explanatory showing the (PID or TID – Thread ID), a truncated timestamp and the system call which in this case is just creating an epoll where the system can add file descriptors to monitor for events.

The second line is more interesting and shows when thread 144523 actually blocks accepting new connections, which is resumed when a request to /hello comes in leading to the accept resumed.

144523 5440.167 <... accept resumed>{<truncated>), sin6_scope_id=0}, [28]) = 11

We can assume now that 144523 is the Acceptor. Notice that once the connection is accepted it returns a number and that is used to reference the socket’s file descriptor (in this case, 11). From Tomcat’s perspective, that is done by Acceptor.run() method. The snippet below presents an excerpt of the run method:

try {

// Accept the next incoming connection from the server

// socket

socket = endpoint.serverSocketAccept();

} catch (Exception e) {

// We didn't get a socket

// commented for brevity

}

Remember the fcntl system call? Here is where the acceptor is asking NioEndpoint to set some properties OR-ing with O_NONBLOCK as explained previously. As one may notice, there is another connection accepted with the ID 12, which I am not sure what this is about (apparently Chrome can open extra connections before sending requests, but I am not sure about it).

Polling for events

Another thread (TID 144522) starts registering interest on input events (EPOLLIN) for the accepted socket number 11.

144522 5440.178 epoll_ctl(9, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 11, \

{events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=11, u64=126985003073547}}) = 0

This call was made when the connection was accepted and the Acceptor invoked setSocketOptions for the new SocketChannel which is an indirect call to the Poller.register method shown below.

public void register(final NioSocketWrapper socketWrapper) {

// this is what OP_REGISTER turns into.

socketWrapper.interestOps(SelectionKey.OP_READ);

PollerEvent pollerEvent = createPollerEvent(socketWrapper, OP_REGISTER);

addEvent(pollerEvent);

}

Then, as the next step it starts waiting for events (here I am logging only the epoll_wait call that happened with timeout 0 which means that the Java selector did not have the chance to be woken up by Acceptor – by registering new events to the Poller).

144522 5440.178 epoll_wait(9, [{events=EPOLLIN, \

data={u32=11, u64=126985003073547}}], 1024, 0) = 1

This call happens within the Poller’s loop that checks for wakeup signal (same code previously shown):

if (wakeupCounter.getAndSet(-1) > 0) {

// If we are here, means we have other stuff to do

// Do a non-blocking select

keyCount = selector.selectNow();

} else {

keyCount = selector.select(selectorTimeout);

}

Later, when the Poller is ready to dispatch a request processing, it removes the interest for input events on the socket 11 as follows:

144522 5440.178 epoll_ctl(9, EPOLL_CTL_DEL, 11, 0x737e05ffe514) = 0

The request processing starts

Then the HTTP request pipeline starts and the worker thread starts reading from the request which is visible in the following system call (notice the first column changed again to TID 144512):

144512 5440.201 read(11, "GET /hello HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: localhost:8080\r\nConnection: keep-alive...", 8192) = 695

144512 5440.218 write(1, "Handling the request in thread: http-nio-8080-exec-1\n", 43) = 43

The write system call here is simply writing to the console, which I have done with a System.out.println from within the Servlet’s service method.

Finally, the response

Yes, it was a long journey. Now, finally the custom thread (notice the new TID 144513) writes the response to connection initially accepted with ID 11. Here is the proof that the Servlet Async mechanism really writes to the right connection.

One may judge me now: “Hey, come on! Isn’t enough to just see that the browser got the response to believe it?”. Okay I get it, but think of this debug as a math proof. A famous logicist once spent years to prove that one plus one equals two, so why can’t I prove that the Servlet works by looking at the Linux system call level?

144513 5440.221 write(1, "Processing async in thread: http-nio-8080-exec-2\n", 49) = 49

144513 5444.231 write(11, "HTTP/1.1 200 ...", 136) = 136

By the way, if I remember well, the logicist I was talking about was Bertrand Russel and the monumental work was Principia Mathematica which was actually the outcome of Bertrand’s and Alfred North Whitehead’s work.

Asynchronous support at the HTTP request pipeline level

This is a short section just to describe a bit of why we have to set the request as asynchronous from within the service method. Again that may seem obvious, but is it? Why can’t you just create the thread and start it anyways without actually marking the request as asynchronous? If you try to do this, by just passing the response to the background task so that it writes to the response when it runs, then that will be the outcome (except for the HelloServlet in my stack trace):

Exception in thread "custom-thread" java.lang.IllegalStateException: \

The response obj. has been recycled and is no longer associated w/ this facade

at o.a.c.c.ResponseFacade.checkFacade(ResponseFacade.java:427)

at o.a.c.c.ResponseFacade.isCommitted(ResponseFacade.java:190)

at o.a.c.c.ResponseFacade.setContentType(ResponseFacade.java:150)

at com.adolfoeloy.HelloServlet$BackgroundTask.run(HelloServlet.java:36)

Marking the request as async with request.startAsync() will bind the AsyncContext with the request and that will be used throughout the HTTP request pipeline in order to make sure the response is kept open for the background task to write the response when it is ready to do so. Here is a very simplified view of what happens when the Servlet is being processed:

The main point here that I want to illustrate is that when the HelloServlet finishes processing it returns potentially before the BackgroundTask completes and the request’s AsyncContext reference will be used by the request pipeline (when returning) to check if the request is async in order to keep the response open and control the async state-machine statuses.

When BackgroundTask completes processing the request pipeline will check and update the async state-machine appropriately and will close the resources after finishing.

Final thoughts

One thing I would like to re-iterate here is that using asynchronous response is not a magical solution that will increase the throughput of your application. If the custom threads also block because of waiting for a long DB call to resolve or because of waiting for a slow third party service, the custom thread pool may as well exhaust until the executor’s queue also reaches the limit and the service just become unresponsive in the same way it would without the asynchronous approach. Again, this is not non-blocking I/O solution and it doesn’t provide backpressure.

Last but not leaset, my purpose with this blog post starts with my intention to consolidate the things I learned while doing my research on Tomcat’s inner workings. I consider this mission acomplished for the purposes I had. However, I also believe that this content may help other curious minds to have a clear picture about what happens when a request is processed by Tomcat and more: that the very common confusion about async vs non-blocking I/O is cleared out by now. If you were patient to read this blog post till this point, thanks for reading it and I hope you have enjoyed as much as I had while writing it.

References

- JSR 315: Java Servlet 3.0 Specification

- JSR 315 Servlet 3.0 Specification Part I

- Comet low latency data for the browser

- Using Asynchonous Servlets for Web Push Notifications

- Discussion about the relationship between Non-blocking I/O support from Servlet 3.1 and the async processing of Servlet 3.0

- Non-blocking I/O using Servlet 3.1 example by Arun Gupta

- Tenfold increase in server throughput with Servlet 3.0 asynchronous processing

- Spring MVC 3.2 Preview: techniques for real-time updates

- Spring MVC 3.2 Preview: Introducing Servlet 3, Async Support

- Java NIO Selector

- epoll Linux man page